Twitter Timeline Height

If our Twitter timelines (tweets by the people we follow) actually extended off the screen in both directions, how tall would they be?

Anonymous

This is a surprisingly tricky question. The answer involves German tanks, human extinction, and the most disputed statistics problem on the internet.

But first, Twitter.

Lots of tweets

The answer obviously depends who you follow. Some people tweet a lot more than others.

@JephJacques, the author of Questionable Content, tweets a lot. His contribution to your timeline will be 36,000 tweets and rising. On the other hand, if you follow people who don't tweet very much, it's possible your timeline to date could fit on a single screen.

According to an analysis by Diego Basch, as of last year the "average" Twitter account had tweeted 307 times and was following 51 people.[1]Diego Basch, Some Fresh Twitter Stats (as of July 2012, Dataset Included) (Dataset not included.) But averages can be deceptive;[2]If Larry Ellison, who made $96 million last year, moves into a typical town of 3,000 people, the average income in that town will double overnight. most Twitter accounts had never even tweeted at all, or have only one follower.

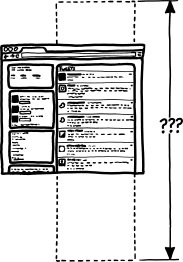

To get an idea of the typical timeline, I asked some friends to take a snapshot of their Twitter homepages and count the rate of tweets at that particular moment. The results covered a wide range—some were seeing 20 tweets per minute, some 20 tweets per month.

Correcting[3]Multiplying by a random number between 0.5 and 1 for the time of day and extrapolating[4]Filling a spreadsheet with numbers until I ran out of columns backward based on Twitter's growth rate, this suggested some timelines currently contain hundreds of tweets and some contain millions.

On my computer's monitor, the average tweet is about 2.4 centimeters high.[5]Citation: I just measured. You can measure, too, but you'll have to use your computer instead of mine. I'm using mine now to type this, so I need to be able to see the screen. This suggests that Jeph Jacques' tweet tower is 900 meters tall—taller than the tallest building—and still growing.

However, Jeph has nothing on @YOUGAKUDAN_00, who tweets many times per minute—usually binary, but sometimes actual words. @YOUGAKUDAN_00 has accumulated 37 million tweets, enough to reach into low Earth orbit.

Combining Diego's July 2012 estimate with the current rate of tweets per day suggests there have been a total of about 345 billion tweets as of October 2013. That means that if you followed every Twitter user, your timeline would be eight million kilometers high. For comparison, here's the Earth, with your Twitter timeline next to it:

Of course ... that's just the part of the timeline below the screen. What about the whole timeline?

Someday, the last person you follow will tweet for the last time. When will that be?

The future

Our timelines aren't really as tall as skyscrapers—even virtually–because Twitter limits the number of past tweets you can see by scrolling. But can we estimate how tall our timelines will eventually be?

Based on human lifespans, it seems likely that most of the accounts you follow will stop tweeting within a century. On the other hand, accounts like @big_ben_clock could keep going for millennia.

But will Twitter last that long?

It's obviously impossible to predict for sure, but there's a strange tool from statistics that might help.[6]Predict the end of Twitter with this 1 weird old tip!

Or might not. It depends who you talk to.

German tank problem

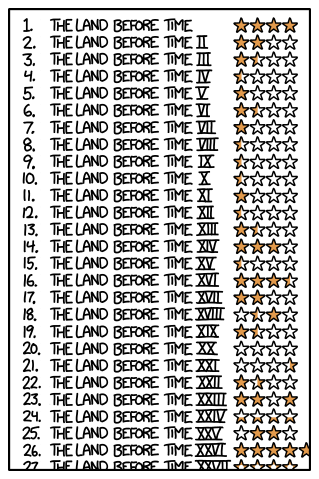

Suppose you're transported to an alternate universe. You open IMDb and load a random page, and the movie that comes up is The Land Before Time XXVII.[7]27

Based only on the title, how many Land Before Time movies do you think there are in this universe? Clearly there are at least 27, and probably more.

Allied troops faced a version of this problem in World War II.[8](A flood of Axis-produced Land Before Time sequels.) German tank parts had serial numbers, many of which were sequential (1, 2 ... N). Suppose they captured a random tank. If they determined it was Tank #27, then they can be sure that the Germans had made at least 27 tanks. It also told them there probably weren't millions of tanks; if there were, they would have been unlikely to get a two-digit serial number.

Of course, the enemy can foil this plan by giving their tanks random large serial numbers. The US actually did that in 1981—the Navy named its elite counterterrorism unit "Seal Team Six" to confuse Soviet spies into thinking there must be at least five other teams out there.[9]Pfarrer, Chuck. "Team Jedi." In SEAL target Geronimo: the inside story of the mission to kill Osama Bin Laden. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2011. Loc 594/3898.

Assuming the numbers are sequential, using clever Bayesian math, you can guess the actual number from a sample of tanks pretty reliably.[10]In addition to the Wikipedia article, there are good discussions of the solution on Statistics Blog and Event Horizon

If you have only a few samples, the math gets a little trickier.[11]The problem is that you're forced to select a "prior"—an initial hypothesis about how likely each number of tanks is. Usually, people just assume there's an equal chance of every number of tanks. But mathematically, this assumption plays fast and loose with the math. The idea of having "an equal chance of getting every number from 1 to infinity" doesn't work in probability; technically speaking, it violates Kolmogorov's Second Axiom. With one sample—as in our Land Before Time problem—the best strategy is probably to take the number you've seen and double it. This suggests that there are probably about 54 Land Before Time Movies.

The idea is that you're likely to be somewhere in the middle of the range—there's only a small chance that you're looking at one of the first or one of the last movies.

Things get weird

If we apply the German tank problem to humans, we can argue that our species will go extinct by the year 2807.

Here's the argument:

Humans will go extinct someday. Suppose that, after this happens, aliens somehow revive all humans who have ever lived. They line us up in order of birth and number us from 1 to N. Then they divide us divide them into three groups—the first 5%, the middle 90%, and the last 5%:

Now imagine the aliens ask each human (who doesn't know how many people lived after their time), "Which group do you think you're in?"

Most of them probably wouldn't speak English, and those who did would probably have an awful lot of questions of their own. But if for some reason every human answered "I'm in the middle group", 90% of them will (obviously) be right. This is true no matter how big N is.

Therefore, the argument goes, we should assume we're in the middle 90% of humans. Given that there have been a little over 100 billion humans so far, we should be able to assume with 95% probability that N is less than 2.2 trillion humans. If it's not, it means we're assuming we're in 5% of humans—and if all humans made that assumption, most of them would be wrong.

To put it more simply: Out of all people who will ever live, we should probably assume we're somewhere in the middle; after all, most people are.

If our population levels out around 9 billion, this suggests humans will probably go extinct in about 800 years, and not more than 16,000.

This is the Doomsday Argument.

Yeah, but that's stupid

Almost everyone who hears this argument immediately sees something wrong with it.

The problem is, everyone thinks it's wrong for a different reason. And the more they study it, the more they tend to change their minds about what that reason is.

Since it was proposed in 1983, it's been the subject of tons of papers refuting it, and tons of papers refuting those papers.[14]Nick Bostrom, A Primer on the Doomsday Argument There's no consensus about the answer; it's like the airplane on a treadmill problem, but worse.

What does this mean for Twitter?

Let's assume the Doomsday argument is valid and apply this reasoning to Twitter. Since there have been 345 billion tweets so far, then the best guess about Twitter's total lifetime is that there will be 690 billion tweets.

At the current rate of 400 million tweets per day, this argument says Twitter has about five years left. And it suggests that there's a 95% chance Twitter will disappear within 45 years.

This certainly sounds reasonable—given the rate of technological change, there's no reason to expect an internet service to stay popular for more than 10 or 20 years.

But ... is the Doomsday argument valid?

If we see Twitter activity winding down in 2018, then will that be evidence in favor of the Doomsday argument? And if so, does it suggest that humanity has only two centuries left?

Probably not. But it depends which statisticians you ask.

On the plus side, they seem to have stopped making The Land Before Time sequels in 2007, so at least we stand a good chance of avoiding that particular scenario.